My research interests

Cognitive control; neuromodulation of cognition; computational modeling

My scientific journey so far

During my PhD (2015-2019) at Leiden University (the Netherlands) I investigated whether the control over our thoughts and behavior can be improved, for example, through the use of supplements that alter brain chemistry or by using non-invasive brain stimulation that changes the brain’s excitability.

I did a postdoc (2019-2020) in Jonathan Cohen’s lab at Princeton University, (U.S.) where I learned to develop biologically-plausible computational models of decision-making that we use to understand how people implement and switch between more focused and flexible mindsets.

I continue this work as a tenured assistant professor back at Leiden University (2021-present). In parallel, I also investigate how our ability to briefly maintain or update information is affected by, for example, brain chemistry or the relevance of this information to oneself.

Recently, I received a project grant from the Gratama Foundation/Leiden University Fund (LUF; 2021) to investigate how our control over the moment-to-moment maintenance vs updating of information is affected by experiences of social adversity such as loneliness.

For more detail on my research, read on.

Dynamics of cognitive control

A major focus of my research is to develop cognitive models that formalize the role, implementation and dynamics of cognitive control. One part of this endeavour is to understand how dynamics of control can account for the stability-flexibility trade-off in attention: the fact that stable focus on one task comes at a cost of slower switching of attention to another task. In work of myself and colleagues (Musslick et al., 2018, 2019; Jongkees et al., 2023) we propose that stronger allocation of control increases the weighting of relevant stimulus inputs in a decision making process (thus improving ‘stability’), but also increases the time necessary to reconfigure control when a shift to a different task is required (thus impairing ‘flexibility’). You can think of this as being located in a ‘well’, as shown above: when a well is very deep, there is strong focus on its corresponding task. While this improves performance on that task and shields it from distraction, it also increases the time and effort necessary to switch to a different task. Conversely, more shallow wells facilitate task-switching but also increase the risk of accidentally leaving a well.

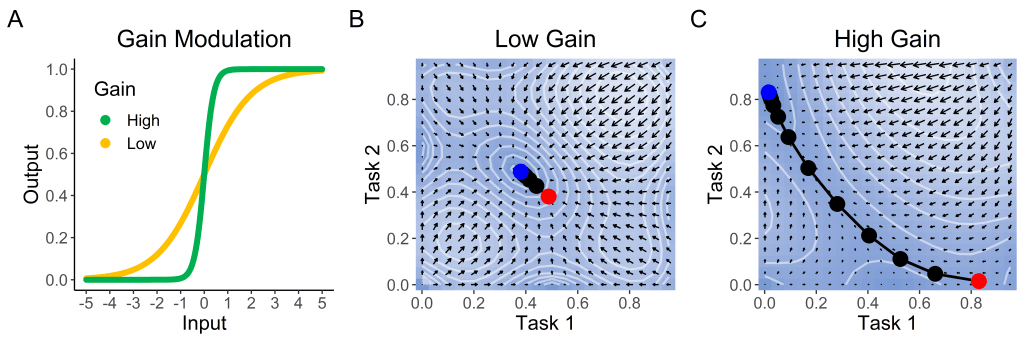

We have formalized these ideas in a dynamical system, where the intensity of control allocation was determined by the gain of task-representing units (Figure 1A). Model simulations show that high gain (corresponding to high intensity of control), as compared to low gain, indeed improves stability (indexed by the maximum level of activation of the relevant task unit and minimum level of activation of the irrelevant task unit) but impairs flexible switching (indexed by the time required for task units to settle into the appropriate activation state during a task-switch; Figure 1B, C). Simulations further show that the optimal intensity of control (in terms of maximizing response accuracy) depends on how much flexibility is required during a task: when task-switches are frequent the optimal intensity of control is lower, and model fitting of behavioral data indicates people adjust their control intensity in line with this model prediction. These findings provide a mechanistic account of the stability-flexibility trade-off and allow for normative, rational predictions on optimal control as a function of a task’s demand for cognitive flexibility.

Figure 1. (A) Effect of gain modulation on the nonlinear activation function of task units, which relates the net input of a unit to its activity state. (B-C) Phase portraits for activity of the task units in response to task cues, under low gain (B) and high gain (C), showing trajectory from prior activation of one task (e.g., red dot for task 1) to the cued task (e.g., blue for task 2). Contour lines and arrows indicate the energy and shape of the attractor landscape after a task switch from one task to the other.